Have you crafted your way out of pandemic stress? If you haven’t already, it’s a good time to pick up a new craft. Making something is a great way to escape the stresses of everyday life, helping to provide a welcome distraction — even if just for a short while.

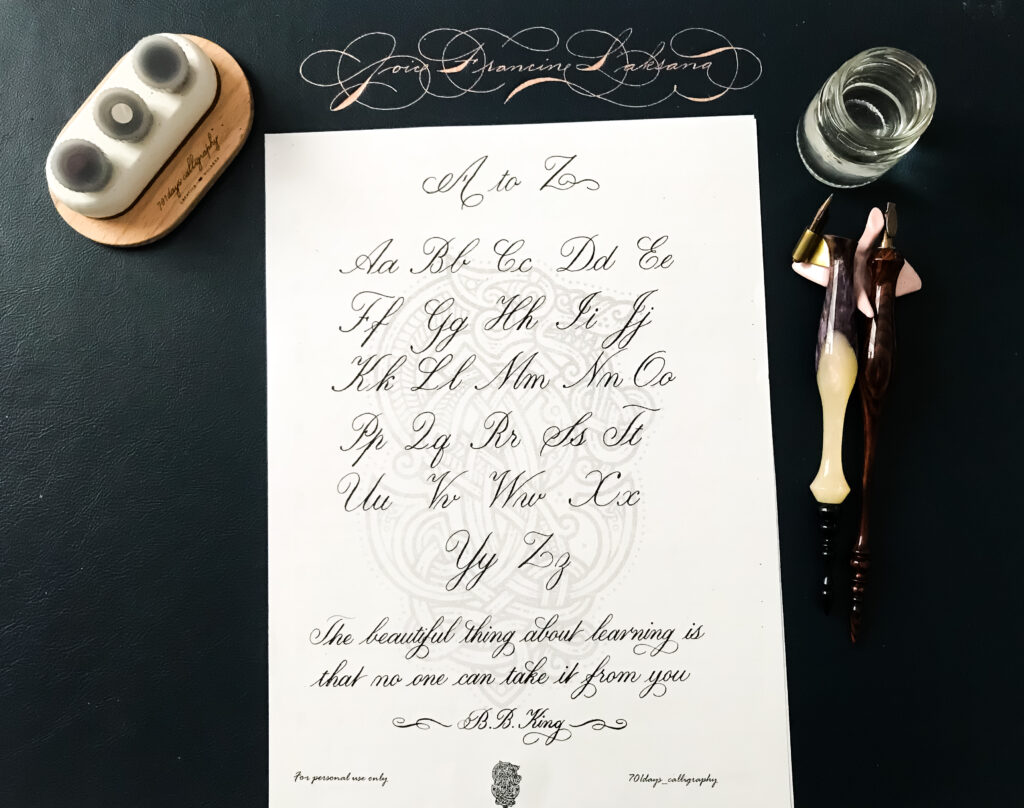

“Crafts like calligraphy keep our hands and minds busy which can be therapeutic,” says Joice Francine, who runs 701days_calligraphy, a western calligraphy as well as Japanese flower art, Hanagami and Ikebana practice, in Jakarta.

Calligraphy and craft with Joice Francine | Photo by: 701days CalligraphyThe creative, from Bandung, set up the workshop years ago as an extension to sharing her passion and bring awareness into this art form. In the wake of Covid-19, Joice has taken her business online to teach people the creative skill through online workshops and calligraphy kits.

Unlike the trend for adult coloring books (hands up if you have one abandoned on a shelf at home), it takes dedication to master the flowing strokes of calligraphy. But that’s all part of the joy of it for this woman – who credits calligraphy with enhancing her lives in very different ways.

Calligraphy is a wonderful intersection of precision and art:

“A perfect match for my design-trained mind and my childhood love for markers, pens, cursive writing, art, and poetry”, says Joice.

“The 1st script I learned was English Roundhand which serves as the entry point for me into the world of calligraphy. English Roundhand has elegant strokes, combined with flowing lines, with balance between thick and thin lines,” Joice said.

“It’s like starting with classical piano style, which will allow easier transition to learn other piano style. Calligraphy could take on basically the same concept as well,” she explains.

“The secret is that calligraphy is an art that requires you to create single strokes, which you connect to form letters and words. It cannot be rushed, and preferably done with a degree of mindfulness,” says Joice.

Starting point

“When I first started out with calligraphy, information was not as widely available, especially in Indonesia. So over time, I self-taught myself through books and references, partaking in workshops which could expand my calligraphy interests,” she said. “I’ve learned how fast-paced this world is and how much we spend time on working and other activities, but allocating very little time for our creative fulfillment.”

“It’s really like the child in me coming out at such times; discovering something that has grown to become an essential part of my life. And then over time, this was shared by teaching as well as through other like-minded calligraphers, thus building a community for us to share and progress together,” she told SELESA.

Joice says the journey has been a few years in the making and now there are calligraphy communities locally which provide advice and workshops for budding calligraphers. “It’s so uplifting and helpful for beginners.

“So if you’re like me and you are seeking an avenue to express your creative needs through calligraphy, I encourage you to head to Instagram and just start going down the rabbit hole of following calligraphy accounts and reaching out, chatting in DM’s, etc,” she says in excitement. “And of course, you’re also welcome to join my community over on Instagram, 701days_calligraphy.”

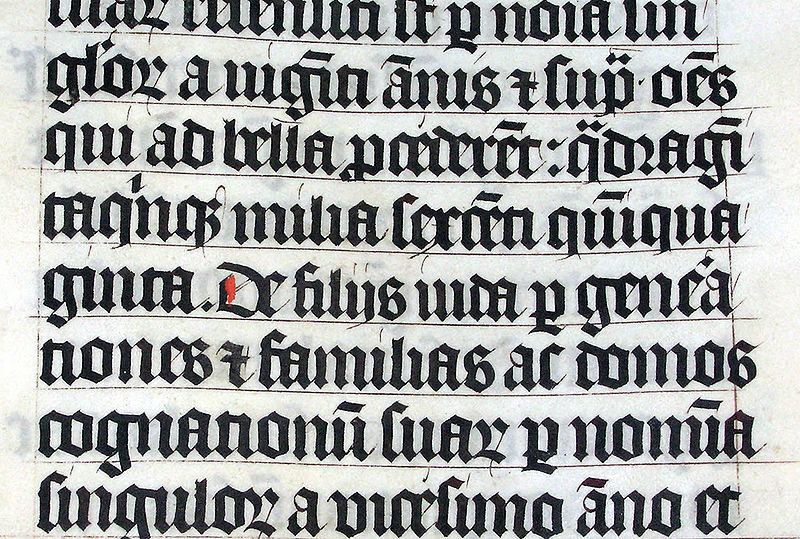

Western Calligraphy: Past Gothic to Modern Italic

Not a lot is known about the origins of Western Calligraphy. What is known is that, in pre-Gutenberg Europe, fonts were just as much a civil technology as tools and weapons. According to the ‘Calligraphy’ book by Claude Mediavilla, in 14th- and 15th-century Florence, the carefully-rendered, but utilitarian, Italic script was the speediest way to formally record information

As a matter of fact, Italic script was a response to the cramped and illegible lettering of the popular medieval book-hand Gothic.

This hand of continuous strokes, allows words to be written without lifting the pen from the paper. Thanks to its rapid execution, it is completely customizable and adaptable to whatever register one wishes to give it, allowing more expressive letterforms.

Calligraphy continued to evolve and in the 18th century, from the Italic, the English Italics—also known as Copperplate—and the art of penmanship were born. A new tool also appears at this time: the pointed pen or expansion pen, with which thick or thin strokes are obtained depending on the pressure exerted.

In these styles, decoration and virtuosity in the handling of the pen take on greater importance than the shape of the letter itself.

Nowadays, calligraphy is experiencing a resurgence. Many calligraphers use the pen as another tool in their work process, and many artists even base their style around the tool itself.

Keeping little hands busy with Ikebana

Ikebana — meaning “arranging flowers” or “making flowers alive” — is a centuries-old Japanese art form that originated as flower offerings at altars. Joice became interested in it after traveling through Japan.

“The motto for Ikebana International is, ‘Friendship through flowers,’ ” Joice said. “The idea is basically that you come together as a group of friends, and you study the art form, and also other Japanese cultural things.”

In Japanese culture, most native flowers, plants, and trees are embedded with symbolic meaning and are associated with certain seasons, so in traditional ikebana, both symbolism and seasonality have always been prioritized in developing arrangements.

Some of the most common elements used are pine and Japanese plum branches around the new year; peach branches for Girls Days in March; narcissus and Japanese iris in the spring; cow lily in summer; and chrysanthemum in autumn.

Since you’re working with live materials in ikebana, the piece has to come together fast. Branches and flowers aren’t as easy to manipulate as pen marks, so making peace with imperfections is often the way to “perfecting” your ikebana piece.

“You kind of have to deal with, for example, if you want a branch to stand a certain way, and it’s not gonna stand that certain way, you either have to give up, or find another branch, or go with it,” Joice said. “At some point you say, ‘I’m just letting go of it and working with it as it is.’”

HANAGAMI: Part Ikebana. Part Origami

It’s the next chapter of Joice Francine’s story about loving Ikebana and loving origami crane. It’s a tale of bringing two passions together, to develop new, innovative creations.

“What’s interesting that there is another pearl in the necklace of Japanese arts – it is Origami,” says Joice. This art of folding paper to make decorative items, is a common indoor entertainment in Japan, and most people learn how to fold an origami crane in their youth.

But paper cranes are starting to become known around the world as a tangible form of prayer for peace or a way to show of support for people facing difficult challenges.

“I love the philosophy behind the origami cranes. It is believed as a symbol that brings hope to the world,” Joice explains.

The story goes to Sadako—the model for Hiroshima’s Children’s Peace Monument, who folded over a thousand cranes in hope of a miracle. Two-year-old Sadako Sasaki was living in Hiroshima when the atom bomb was dropped. Sadly, ten years later, she was diagnosed with leukemia, also known as “atom bomb disease.

As the crane is a symbol of long life, strings of 1,000 paper cranes, or senbazuru in Japanese, are often offered as a get-well gift expressing hope for a person’s recovery, as a sign of support for natural disaster victims, or encouragement for sports teams, or even weddings.

Arisen in Japan, with roots in Ancient China, Origami has the fine charm of eastern philosophy that impels one to find beauty in simple things.

“By combining our fascination with these remarkable arts, I began to create paper art-flower arrangements. At that time, I wanted to think up a special descriptive word for them. I took two words: “Hana (flower)” and “Origami,” united them, and the beautiful word “Hanagami” resulted. Since then the term HANAGAMI is widely used in our community especially among those who love floral themes,” she explains.

Jump on the dried flower trend

It’s no secret that flowers are a great pick-me-up, but fresh flowers could only last a short while, which could be one of the reasons preserved flowers are sometimes preferred as a longer lasting alternative.

“Preserved flower arrangements are in demand and growing in popularity” says Joice, “The idea of buying something that you can enjoy, which last, that you could re-arrange, is a great convenience,” says Joice. “I could always take the preserved flowers available, mix and match and make an entirely new creation anytime.”

Making arts and craft today

Anyone who practices arts today knows well that building relationships is at the core of the practice—relationships between materials, between students, and between teachers and their pupils.

The flexibility and variation that Joice’s style allows for has made it a favorite and a staple in her art and craft workshops today. At the core of Joice’s art classes is a freestyle system, where the maker uses their knowledge of form, color, and line from previous practice to develop new arrangements that don’t necessarily adhere to traditions.

Joice was firm in her conviction that a successful lifelong art practice requires curiosity, not complacency. “We must strive to develop into artists with breadth and depth instead of remaining comfortable in our artistic niche,” she said. “Our creations should vary. If we do not venture out, we will never become outstanding artists.”

Joice ‘s Calligraphy, Hanagami and Flower Dome workshops are available through Arts and Culture, exclusively on SELESA.